Core Language of Form

Deborah Adams Doering has developed a "core language of form," a small group of basic marks that both distills complex concepts and elaborates on their implications. The marks are kindergarten-simple and, at the same time, fertile enough to introduce us to concerns about human consciousness and our connection to Nature, as well as our uses of technology. By terming it "core," she posits the idea that there is something fundamental there, something accessible to all humans, in any time. If it is at our core, it is something at our very center and something universal, a something that Doering's work asks us to explore. Her core language is not a blatant, simplistic form nor is it a stick-figure sort of abstraction that can trivialize complex matters. It isn't writing, but it is a form of language and, if pursued, a form of revelation.

Human life is gaining layers of complexity, and art should reflect that. Yet, art's task remains, in part, to search for fundamentals and commonalities that link us to each other and the world that we share. Art should tell us something about ourselves and our time, about the world we inherited and the one we create. When a work of art comes into existence, we seek to know its genesis and then its progression, asking of it the same questions we ask of ourselves, as in Gauguin's title for his painting, "Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?" These questions about meaning are often asked of artists, and certain works of art, Doering's among them, deal with these issues more urgently.

Doering understands that her enquiries into the essentials of our world have precedents and that she joins a quest undertaken by other artists and thinkers. Among her influences is the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) whose mature paintings of vertical and horizontal lines, primary colors and black and white are among the iconic images of the 20th century. For Mondrian, the utter simplicities of his forms and compositions were indicative of truths of which humans could become conscious.

Like Mondrian, Doering is interested in the invisible, yet she is deeply rooted in the actualities of our existence. Her earlier work was involved in scenes from nature, contemporary culture, or family life that have a prosaic familiarity. Some of these works were rendered in colored squares that mimicked digitization, forcing the viewer to make them "sensible." Her own evolution led her to refine her art until she arrived at her mark-making system, grounded in simple visual forms.

For Doering, there are four fundamental forms: the vertical line, the horizontal line, the circle, and the swash. The swash (sometimes called a tilde) suggests the movement between the first three forms, the transformation of straight to circular and back again. In Doering's vocabulary, the swash can represent a movement through space from one position to another. A swash intimates variations and combinations that straight lines and circles do not. It's full of indeterminates and potentialities.

Doering has called her forms "code." Codes run the world. The most obvious one today is the fundamental code of computing: ones and zeros. One of the confounding realizations about contemporary life is the fact that all of the networks, the information, the numbers and symbols that make up human knowledge come down to ones and zeros. And yet, the sequences and spacings of these ones and zeros, the strings of information that make a web, are all marks and place-holders for other realities. It seems likely that our time will be defined by the computer, especially its use as an image-making tool. Thus, she has elucidated, as an art form, one of the most daunting issues at the center of the technological transformation of our time.

Doering recognizes how crucial it is for art to speak for its own time yet also transcend it. She refers to technology and its ubiquitous presence in our lives, but her art isn't, itself, technology. Looking at art is not just downloading information; it's a goad to peer beyond the obvious or the utilitarian. Art is an incentive to try to understand something beyond an "application." Seeing the connections to computing languages is one way to approach Doering's work, but her art can pull us past this familiarity toward more complex and fruitful thoughts.

Doering's code evokes both the ancient and the advanced: from the cuneiforms of Assyrian clay tablets to the pixels of jpegs. Humans have always used codes to understand our world and to communicate with each other. Writing is the most obvious example. Letters and numbers are codes. But Doering's works are not ones that we can "read." That is part of the reason why we don't call them information, but instead we call them art. Codes are systems that enable us to penetrate into the invisible world, a world that includes the human mind. Codes at first glance may be unreadable.

A sequence of such symbols or a field of coded forms, though indeciperable, often has a physical beauty that appeals to us immediately, viscerally, as when a person who doesn't read Japanese looks at a page of calligraphy. Doering's works are visually beguiling, but soon we start to deal with them on a different, interpretive level. We keep looking because they intrigue us and make us start to wonder and start the de-coding. It's clear they aren't random and that they hold meaning. When we start to contemplate that meaning is when movement begins.

Doering has said that her art is about codes and movement. Movement is something that happens in both the body and the mind, and both can participate in a shift in states of being, an experience Doering embraces and, at times, encourages. Art can fulfill many functions in human life, but one thing it certainly does at its highest level is the

elevation of our consciousness, taking us to a new strata of our own humanity. As part of the idea of incorporating intellectual and physical movement, Doering has taken her code to a new scale.

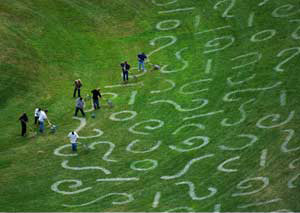

Recently, her code has been drawn onto the landscape where the lines and circles and swashes can be literally walked, traced with the body, as well as seen from across a field or scanned from an airplane. Now we can be encircled by the code or view it from afar, and we can contemplate microcosm and macrocosm, microbe and celestial orb in a new way.

A characteristic of human beings is our consciousness, a way of thinking and being that can encode vast stores of information in ones and zeros. as well as decode them for dissemination. Doering has emphasized that our consciousness, despite our

distinct expressions of it, is still part of Nature.

To imagine that we are separate from the world around us is to deny and endanger our humanity. Harming the earth is harming ourselves; the failure, as Doering has stated, to "synchronize our technological codes with Nature" will compromise our future and will surely affect any hope of living in harmony with Nature. Doering has explained that she hopes her code "will connect human consciousness with the consciousness of all that surrounds us." When we experience her code bodily, moving along its lines on the earth, we allow the artist to act on our own personal consciousness. Part of that shift in our state of being is the realization that our code and the earth's code are intertwined, that we join all of creation within a grand, dynamic circle. As complex as this concept can be when elaborated on, it is also a concept of primal simplicity, as singular as Doering's core language of form.

Lea Rosson DeLong

Lea Rosson DeLong holds a Ph.D. in the History of Art from the University of Kansas.

She has curated Shifting Visons: O'Keeffe, Guston, Richter and Chemistry Imagined:

A Collaboration of Art, Science and Literature.